By Dino Ramos (ESR 11 at University of Granada), Andrew Torres (ESR 3 at Natural History Museum London) and Dedi Parenden (ESR 17 at Hasanuddin University)

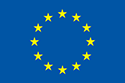

COVID-19 has made working in the field still out of grasp for most of the ESRs and for many months we have all been longing for the day when we can dive into the warm waters of the tropics (Figure 1). While it is still too early to predict when we might be able to dip our toes into Spermonde’s not-so-crystal-clear waters, with our colleagues from Hasanuddin University (UNHAS) on-site, we can start setting up sampling devices to help address a very basic question: “What organisms can we find in these coral reefs?”.

Figure 1. Warm waters of the tropics. We’ll get there, buddy.

Invisible species richness

It is a simple question, but not an easy one to answer. The Spermonde Archipelago is a well-studied area and ever since the days of exploration, scientists and naturalists have been cataloguing its diverse and colorful marine life. Located almost at the geographic heart of the Coral Triangle, one can surmise the sheer scale of biodiversity that this group of islands may contain. It is likely that most of the obvious (i.e. large and charismatic) flora and fauna have already been recorded. However, the diversity of coral reefs is also a function of the many nooks and crannies formed by their complex three-dimensional structure. These also happen to be where our microsnails and coralline algae are expected to be the most diverse. Common survey methods such as the underwater visual census do not necessarily include these hidden microhabitats. It can also be quite tricky to sample the shy organisms all cozied up in the corals without totally wrecking their homes apart. How then can we find out who resides in these mysterious, hard-to-reach spaces? We use our ARMS.

Artificial ‘hotels’ for reef creatures

Autonomous Reef Monitoring Structures, or simply ARMS, are designed to simulate the cryptic spaces in coral reefs. They are made of stacked PVC plates (Figure 2) and fastened securely to the ocean floor amid coral reef habitats. Think of them as tiny apartelles for small marine life to check into. Each “floor” provides space for organisms to occupy. Floors alternately contain dividers to create either small rooms or larger floor spaces to settle onto. The longer these units are left in the ocean, the more ecological succession can take place to passively create different niches and accumulate more and more organisms (and organismal interactions!) through time (Figure 2c). These will represent at least part of the cryptic diversity present in the turbid reefs that we aim to investigate.

Figure 2. a) Autonomous Reef Monitoring Structures (ARMS) schematics from NOAA; b) ARMS units constructed at the University of Hasanuddin (UNHAS) ready to be deployed (photo by Halwi Masdar); c) A potential recruitment outlook in ARMS after three years.

With a little bit of help from our Indonesian friends

4D-REEF has a great collaboration with researchers and students from UNHAS, which shows even more value in these difficult times when we are unable to travel from Europe to Indonesia ourselves to deploy these ARMS. Now the rainy season is over, a group of UNHAS students went into the field to deploy 18 ARMS at turbid coral reefs near 6 islands which range in levels of turbidity. The distance of each of the six islands to the mainland and Makassar city varies. Some are really close and can be reached in 10-15 minutes by using a local community boat, while the farthest location, Langkai Island, is about 2 hours by boat. The field team cannot visit all islands on the same day, so it takes 4-5 days to visit all the research locations.

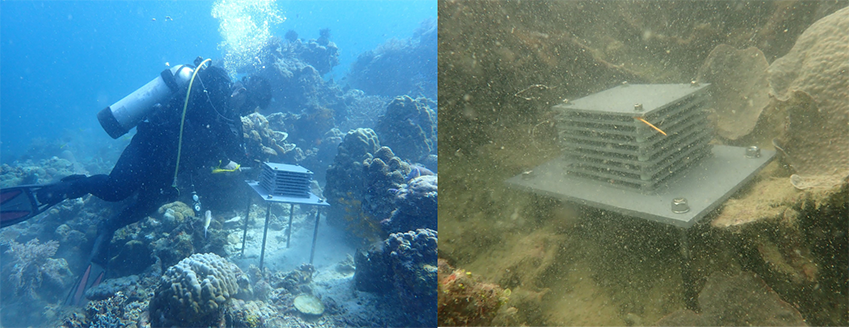

DIY underwater

The team, consisting of 5 scuba divers, is working hard under water using hammers, stakes, wrenches, nuts and bolts, to install the ARMS (Figure 3). Data about the environment is collected at the same time as well as a range of water quality measures. Water temperature and light loggers are also installed at the research sites, which will give us more information about the variability of the water conditions over time. During the ARMS deployment, all loggers that were installed a few months ago were checked and reloaded. All activities ran smoothly and without obstacles, because of good preparations, fairly good weather conditions and quite calm seas. We will regularly check whether the ARMS are still in place, and continue to read out the logger data.

Figure 3. Deployment of ARMS in the waters of the Spermonde Archipelago by our colleagues from UNHAS. The images clearly show the differences in turbidity between different sites.

Connecting to global efforts

The use of ARMS is a revolutionary way of capturing snapshots of reef biodiversity and how these are shaped by different environmental conditions. The dimensions of the ARMS units and its protocols are standardized according to the guidelines provided by the Global ARMS Program. So one of the many advantages to using ARMS is the comparisons we can make with the existing network of ARMS projects. Because of the reproducibility of ARMS, it allows us to contextualize our results on a much wider scale. And with the rapidly declining health of reefs around the world, it has become a very important and helpful tool to employ in understanding the complex ecology of our reef organisms. We are grateful that with the help from our Indonesian colleagues we can start collecting data despite not being able to travel to the field ourselves!